This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

The sewing machine wasn’t born from a single inventor’s workshop—it emerged from decades of competing patents, courtroom battles, and incremental breakthroughs that transformed how humanity clothes itself. While Thomas Saint filed the first patent in 1790, his design never left the drawing board.

The real revolution began when inventors like Barthélemy Thimonnier, Elias Howe, and Isaac Singer turned theoretical concepts into practical machines that could outpace even the most skilled seamstress. Their inventions didn’t just mechanize stitching—they reshaped global industry, created new social classes, and made affordable clothing accessible to millions.

Understanding when the sewing machine was invented means tracing a timeline of ambition, rivalry, and innovation that redefined manufacturing itself.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- When Was The Sewing Machine Invented?

- Early Attempts at Sewing Machine Design

- Barthélemy Thimonnier’s Pioneering Work

- Elias Howe and The Lockstitch Revolution

- Isaac Singer’s Commercial Success

- The Sewing Machine’s Impact on Industry

- Social and Economic Effects of Sewing Machines

- Evolution of Sewing Machine Technology

- Lasting Legacy of The Sewing Machine

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- The sewing machine emerged through decades of competing innovations from 1790 to 1851, with Thomas Saint’s first patent, Barthélemy Thimonnier’s practical chain-stitch design, Elias Howe’s lockstitch mechanism, and Isaac Singer’s commercial breakthrough each contributing essential advancements that transformed theoretical concepts into viable manufacturing tools.

- Howe’s 1846 lockstitch patent revolutionized durability by interlocking two threads within fabric layers at 250 stitches per minute, while Singer’s improvements—including the continuous four-motion feed mechanism and presser foot innovations—combined with installment payment plans to make machines accessible to working families and spark the mass production era.

- The mechanization of sewing slashed garment production time by over 90% (reducing shirt assembly from 14.5 hours to 1.25 hours), democratized clothing accessibility by dropping prices dramatically, and transformed the textile industry from scattered home workshops into centralized factory systems that redefined labor, consumer spending, and fashion cycles.

- The sewing machine’s legacy extends beyond the $1.11 trillion global textile market it helped create, as modern innovations integrate automation, IoT connectivity, and AI-driven precision—proving that technological advancement amplifies rather than replaces craftsmanship while continuing to reshape manufacturing across industries from automotive upholstery to smart textiles.

When Was The Sewing Machine Invented?

The sewing machine wasn’t born in a single moment—it emerged through decades of experimentation, false starts, and competing visions. You’ll find that pinpointing its “invention” depends on how you define a working machine versus a commercially viable one.

Let’s trace the key milestones that brought this revolutionary tool from concept to reality.

Timeline of Key Inventions

You’ll find the history of sewing machines unfolding through decisive moments: Thomas Saint filed the first machine patent in 1790, trailblazing sewing innovations. Barthélemy Thimonnier built the first practical chain-stitch machine around 1829–1830. Then came Elias Howe Jr.’s lockstitch advancement in 1846, followed by Isaac Merritt Singer’s commercial triumph in 1851—milestones that reshaped the evolution of manufacturing technology forever.

The development of sewing machines is well documented on sewing machine timelines.

Defining The Modern Sewing Machine

Building on those early breakthroughs, the modern sewing machine stands apart for its lockstitch technology—using two threads to create secure, adaptable seams. Automatic stitching and enhanced fabric feed systems define today’s machines, letting you stitch anywhere on the fabric.

Singer sewing machine innovations standardized these mechanics, shaping the evolution of manufacturing technology and transforming the history of sewing machines forever.

The sewing process relies on the needle mechanism to create consistent stitches.

First Patents and Prototypes

After lockstitch technology set the standard, the story of sewing machine history turns to patent history and early designs. Thomas Saint’s 1790 patent marks the first leap, followed by inventors like Barthélemy Thimonnier and Elias Howe.

Their machine prototypes laid the groundwork for sewing innovations, each profile reflecting the unyielding quest for reliability, speed, and practical utility.

Early Attempts at Sewing Machine Design

Before the sewing machine became a household staple, it took decades of trial and error to even prove the concept could work. You’ll find that the earliest inventors weren’t just tinkering with thread—they were wrestling with fundamental questions about how to mechanize something as delicate as a stitch.

The sewing machine emerged only after decades of trial, error, and wrestling with how to mechanize something as delicate as a stitch

Here’s where the journey really began, with three pioneers who laid the groundwork long before commercial success arrived.

Thomas Saint’s 1790 Patent

You’re standing at the birth of mechanized stitching: Thomas Saint’s British Patent No. 1764, granted July 17, 1790, marks the first detailed sewing machine design in history.

This London cabinet maker envisioned a chain-stitch apparatus for leather and canvas—boots, saddlery, sails—driven by hand-cranked cams coordinating awl, thread carrier, and looper.

Though no original prototype survived, William Newton Wilson’s 1874 reconstruction proved Saint’s Industrial Revolution-era innovation was genuinely buildable.

Karl Weisenthal’s Needle Innovation

You’ll discover a critical needle innovation that predates full machines: Charles Frederick Wiesenthal secured British Patent 701 on September 20, 1755, for a two-pointed needle designed for fabric ornament and Dresden-style needlework.

This inventor’s mechanical stitch aid—sharpened at both ends—eliminated needle reversal during embroidery, prefiguring eye-midpoint concepts later adopted in sewing machine history.

Though never commercialized, Wiesenthal’s contribution marked a critical turning point in sewing machine inventions and technological advancement.

John Knowles and John Adams Doge’s Machine

In 1818, Vermont innovators John Knowles and Reverend John Adams Doge built what stands as America’s first real claim in sewing machine history—a prototype that could form stitches but collapsed under routine use.

This American invention managed only short seams before mechanical failures forced laborious re-setup, revealing early prototypes’ struggle to synchronize needle, thread, and feed.

Though neither patented nor manufactured, their effort secured historical significance as a documented waypoint in sewing innovations and technological advancement preceding Thimonnier’s and Howe’s breakthroughs.

Barthélemy Thimonnier’s Pioneering Work

While early inventors sketched ideas on paper, Barthélemy Thimonnier actually built a machine that worked—and worked well enough to threaten an entire industry.

In 1829, this French tailor introduced the first practical sewing machine that could produce consistent stitches at scale. His invention didn’t just advance the technology; it sparked a conflict between progress and tradition that would shape the future of garment manufacturing.

The 1829 Chain Stitch Machine

You’re witnessing a pivotal moment in Sewing Machine History. Barthelemy Thimonnier’s 1829 Chain Stitch machine—powered by foot treadle and built with wooden framing—changed everything during the Industrial Revolution with its hook-tipped needle design and tambour-style stitch formation.

- Mechanical Innovations: Vertical reciprocating needle synchronized with spiral looper through timed gears

- Fabric Feed: Manual advancement between stitches, limiting speed yet delivering embroidery-like seams

- Industrial Impact: First practical Sewing Machine achieving consistent mechanized stitching

Impact on French Garment Industry

By 1830, you’re looking at roughly 80 chain-stitch machines running in Thimonnier’s Paris workshop under royal contract—France’s first machine-based garment factory. This advancement slashed production time from 14.5 hours per shirt down to about 1.25 hours, cutting uniform costs to one-third of hand-sewn equivalents.

Mass Production suddenly became viable in French Fashion, transforming Garment Production and accelerating Industrial Revolution-era Textile Industry mechanization across urban Garment Industry centers.

Challenges and Backlash

Mechanization fears sparked violent labor unrest in 1831 when roughly 200 tailors stormed Thimonnier’s Paris workshop, smashing dozens of machines they viewed as threats to livelihoods. This targeted assault on innovation and technological advancement effectively halted France’s early mechanized garment deployment.

The incident foreshadowed broader patent disputes and worker exploitation tensions that would define the Industrial Revolution and textiles social changes and industrialization across Europe.

Elias Howe and The Lockstitch Revolution

While Thimonnier proved the commercial potential of mechanized sewing, the real advancement in durability and strength came from across the Atlantic.

In 1846, Elias Howe patented a machine that would fundamentally change how fabric pieces were joined together. You’ll see how his lockstitch design sparked both technical innovation and fierce legal controversy that shaped the industry’s future.

1846 Patent and Technical Advancements

On September 10, 1846, Elias Howe secured U.S. Patent No. 4,750—a turning point for sewing machine design and development during the Industrial Revolution and Textiles era. His lockstitch design introduced mechanical enhancements that redefined innovation and technological advancement:

- Eye-pointed needle combined with a shuttle mechanism for durable two-thread interlocking

- Automatic feed system advancing fabric consistently for uniform seams

- 250 stitches per minute capacity, outpacing hand-sewing teams

Patent enforcement later generated substantial royalties, cementing Howe’s influence on sewing machine innovations.

Lockstitch Mechanism Explained

Elias Howe’s lock stitch innovation wove elegance into engineering: you see two threads—upper needle and lower bobbin—interlocking inside fabric layers for class 301 durability. Unlike chain stitch’s single-thread weakness, this design relied on precise hook design to capture the needle loop during ascent, while balanced thread tension and stitch balance prevented knot migration.

That loop formation timing delivered sewing speed of 250 stitches per minute, transforming sewing machine design and development beyond earlier weaving-inspired sewing technology.

Legal Battles and Recognition

Howe’s advancement sparked fierce Patent Disputes when manufacturers copied his lockstitch without permission. By the early 1850s, Court Rulings affirmed his Intellectual Property rights, forcing Isaac Merritt Singer and rivals into Licensing Agreements that reshaped Innovation History. You’ll see how this legal victory established Industry Standards:

- $200,000 annual Royalty Fees flowed to Howe after court wins

- The 1856 patent pool unified four major firms

- His Patent remained enforceable until 1867, cementing his legacy

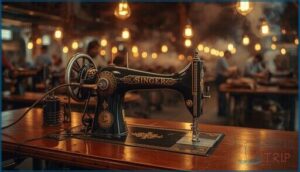

Isaac Singer’s Commercial Success

While Elias Howe’s technical innovation laid the groundwork, it was Isaac Singer who transformed the sewing machine from a promising invention into a household revolution.

Singer didn’t just enhance the mechanics—he reimagined how these machines could reach everyday people and reshape entire industries. His approach combined smart design improvements, strategic business moves, and a vision for making technology accessible to the masses.

Improvements to Sewing Machine Design

You’ve seen how Singer’s technical refinements elevated the sewing machine into a tool of real mastery. Isaac Merritt Singer refined Elias Howe’s lock stitch design by introducing a continuous four-motion feed mechanism that moved fabric smoothly beneath the needle.

His presser foot innovations reduced slippage during multilayer stitching, while introducing zigzag stitch capability expanded creative possibilities—setting the stage for the development of sewing machine technology that would soon integrate electronic control systems.

Founding of Singer Manufacturing Company

That technical vision required more than workshops—it demanded industrial scaling. In 1851, you witness Isaac Merritt Singer and lawyer Edward C. Clark establish I. M. Singer & Co. in New York, utilizing Singer’s August patent to build a corporate structure resilient enough to survive the patent wars.

By 1865, renaming it Singer Manufacturing Company formalized your command over what had become the world’s largest sewing machine enterprise, anchored by the 1863 Elizabeth, New Jersey manufacturing site.

Making Machines Accessible

Beyond engineering, you needed affordability. In 1856, Singer Manufacturing Company introduced installment payment plans—weekly payments between $2 and $10—that tripled sales within the first year. Credit options and machine rentals transformed a $125 appliance into an accessible tool for working families.

Isaac Merritt Singer’s financing strategies, paired with door-to-door demonstrations and retail showrooms, turned mass production into a household revolution.

The Sewing Machine’s Impact on Industry

Singer’s commercial triumph was only the beginning—the real revolution happened when sewing machines hit factory floors and changed how the world made things.

You’re about to see how one invention reshaped entire industries, from textile mills to unexpected places. Let’s look at the three major ways sewing machines transformed manufacturing and production.

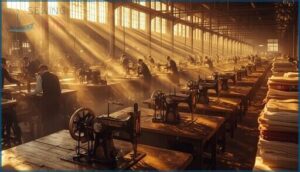

Transformation of Textile Manufacturing

You’ll find that sewing automation transformed Textile Innovation by shifting production from scattered home workshops into centralized Factory Systems. By 1870, Manufacturing Efficiency gains—machines stitched 640 stitches per minute versus 23 by hand—accelerated Industrialization and the Evolution of Textile Manufacturing.

This leap in Manufacturing Technology fueled Industrial Growth, consolidating labor under one roof and redefining the Textile Industry’s entire structure for Mass Production.

Rise of Mass Production in Garments

You’re witnessing Industrialization’s boldest move: by the late 1840s, lockstitch Sewing Innovations ignited Mass Production in the Garment Industry. Factory Systems slashed shirt assembly from 14 hours to just 1.25 hours—a 93% time cut—while one New Haven plant quadrupled labor productivity with 400 machines.

These Manufacturing Technology breakthroughs in Textile Manufacturing turned ready-to-wear from a niche into a mass market, doubling output value between 1880 and 1889 through relentless Innovations in Clothing Production.

Expansion to Other Industries

You’ll recognize Industrial Applications beyond garments as the sewing machine’s true reach: by the early 20th century, Automotive Upholstery, Furniture Manufacturing, and Technical Textiles became essential Non-Apparel Markets.

This Technological Advancement powered airbags, seat belts, and conveyor belt assemblies—Mass Production through Automation that transformed Industrialization itself.

Innovation in these sectors now drives nearly half of all industrial sewing demand globally.

Social and Economic Effects of Sewing Machines

The sewing machine didn’t just transform how clothes were made—it reshaped who could afford them, who made them, and what society valued.

You’ll see how this single invention rippled through economies, opened doors for workers (especially women), and redefined the very fabric of daily life.

Let’s explore the social and economic shifts that followed this mechanical revolution.

Changes in Clothing Accessibility and Affordability

Machine sewing unlocked a revolution in clothing accessibility that reshaped consumer spending and fashion trends forever. By slashing production time for a men’s shirt from 14.5 hours to just over one hour, mass production drove clothing prices down dramatically—American ready-to-wear output jumped from $40 million in 1850 to $70 million by 1870. You could now afford what once demanded a tailor’s custom premium:

- Shirt production time plummeted over 90%, enabling factories to flood markets with affordable garments

- Frock coat assembly dropped from 17 hours to 2.5 hours, making tailored-looking styles accessible across classes

- Ready-wear menswear surged in the late 1840s–1850s, shifting consumers from custom orders to standardized retail

- Household sewing machines reached 500,000 units annually by the 1870s, with Singer’s $5-down installment plans democratizing ownership

- Catalog pricing fell to $10.45 by 1902, placing garment self-sufficiency within reach of working families

This cascade transformed the garment industry and clothing production landscape. Mass production didn’t just lower prices—it accelerated fashion cycles, expanded consumer choice, and redirected household budgets toward variety over scarcity.

The impact of sewing machines on society extended beyond textiles: mechanized stitching slashed shoe labor costs from 75 cents to 3 cents by 1880, producing 125 million pairs by 1895. Ready-to-wear became the norm, not the exception, as inexpensive machine-made apparel replaced home sewing by the 1920s. You were witnessing a fundamental shift—from clothing as a laborious necessity to fashion as an accessible expression of identity and aspiration.

New Job Opportunities and Women’s Roles

The sewing machine’s promise of women empowerment collided with harsh industrial realities—New Haven factories slashed hand sewers from 2,000 to 400 by 1860, yet survivors earned subsistence piece rates despite 16-hour days.

Job creation paradoxically displaced many, while Singer’s installment plans and training academies opened sewing careers and pathways for female entrepreneurs traversing the mass production revolution’s uneven terrain.

Influence on Fashion and Society

Beyond factory floors, you witnessed fashion’s democratization as machine production compressed design-to-market cycles and standardized sizing. By the 1880s, most men bought ready-to-wear garments, reflecting mass production’s cultural impact—clothing shifted from artisan craft to industrial output, redefining social status markers.

The garment industry’s transformation accelerated fashion trends while household budgets freed resources once absorbed by custom sewing, fundamentally reshaping cultural consumption patterns.

Evolution of Sewing Machine Technology

The sewing machine didn’t stop evolving after Singer’s innovation—it kept transforming as new technologies emerged and demands shifted. What began as hand-cranked mechanical devices eventually gave way to electric-powered machines that changed how people worked at home and in factories.

You’ll see how this technology adapted across different settings, bringing speed and precision to anyone who needed it.

Transition From Manual to Electric Machines

By 1889, Singer launched electric motors for sewing machines, initially as external add-ons to treadle frames before full integration improved machine safety and power efficiency. You could regulate speed via foot-controlled rheostats, reducing physical strain while boosting output.

This innovation marked a turning point in industrial electrification and sewing automation, enabling mechanization that reshaped the garment industry and spurred mass production through enhanced productivity and innovation.

Adoption in Modern Homes and Factories

Following electrification, you witnessed sewing machines reshape both home and factory landscapes. Automation and smart sewing systems now drive mass production efficiency in the garment industry, with mechanization reducing manufacturing costs by 20% and enabling innovation across textiles, home automation, and modern embroidery applications.

By 2021, U.S. households spent an average of $4.33 on machines, while industrial segments captured 45.8% of the global market through factory robotics and industrial IoT integration.

Lasting Legacy of The Sewing Machine

The sewing machine didn’t just change how we make clothes—it rewired entire economies and continues to shape industries today. From its humble beginnings in the 1800s, this invention sparked a technological revolution that’s still unfolding in workshops and factories worldwide.

Let’s explore how this powerful tool left its mark on global markets, pushed the boundaries of innovation, and what’s coming next in sewing technology.

Influence on Global Textile Markets

You can trace today’s $1.11 trillion global textile market directly to the lockstitch revolution. By 2033, that figure will hit $1.61 trillion—powered by Asia-Pacific’s manufacturing dominance and the mechanized stitching that first enabled mass production.

The sewing machine didn’t just spark the Industrial Revolution’s garment industry; it created enduring market trends linking fiber production, industrial growth, and fashion democratization across continents.

Technological Innovation and Craftsmanship

You’re witnessing a paradox: as Machine Learning and Automated Stitching drive Digital Fabrication in Smart Textiles, the history of sewing machines reveals that Technological Innovation actually elevated Craftsmanship.

Howe’s 1846 lockstitch required skilled machinists for adjustments, while Singer’s Industrial Revolution factories employed 16,000 workers mastering Advanced Materials—proving that automation doesn’t erase artistry; it transforms it into precision-guided mastery.

Future Trends in Sewing Technology

You’ll see Automation Trends and IoT Integration reshape every stitch—the sewing robot market hits $10 billion by 2035, while AI Stitching and vision systems already streamline fabric handling without human oversight.

Smart Fabrics demand Computerization that merges Fashion and Technology through real-time analytics.

This Robotics Innovation balances Sustainability and Craftsmanship, proving Artificial Intelligence amplifies precision rather than replacing it.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who invented the sewing machine in 1790?

Thomas Saint, an English cabinetmaker, received the first sewing machine patent in His pioneering design targeted leather goods manufacturing, establishing the foundational blueprint for mechanical stitching before the Industrial Revolution transformed textile production.

When were sewing machines first used in the home?

Sewing machines entered homes in the 1850s when Isaac Singer introduced hand-cranked and treadle models with installment plans, making domestic machine use affordable—by 1875, 34% of Massachusetts working-class families owned one.

How much was a sewing machine in the 1800s?

Like buying a horse when cars arrived, owning a Sewing Machine in the early 1800s demanded serious coin—Thimonnier’s French machines fetched 50 francs in the 1830s, while American Singer sewing machines hit $125 by 1852, roughly $3,700 today, until payment plans cracked Consumer Affordability wide open.

When did the first Singer sewing machine come out?

You’ll find the first Singer sewing machine came out in 1851, when Isaac Singer received U.S. Patent No. 8,294 on August 12—launching the Singer Corporation and revolutionizing the Industrial Impact Analysis landscape forever.

How did ancient civilizations sew before sewing machines?

Picture bone awls piercing leather 70,000 years ago—your earliest ancestors mastered ancient stitches using prehistoric tools and primitive threads from sinew.

By 25,000 years ago, eyed needles revolutionized sewing techniques, enabling fitted early fabrics.

What materials were early sewing machine needles made from?

You’ll find that early sewing machine needles were crafted from high carbon steel—drawn through dies, hardened, and tempered.

Elias Howe and Isaac Singer relied on metalworking techniques that transformed ancient materials into precision tools for their patented inventions.

Did sewing machine invention affect fashion trends?

You access a wardrobe when production scales. Mass production reshaped the garment industry, letting ready-to-wear styles reach everyday consumers and accelerating fashion trends—transforming clothing from exclusive craft into vibrant cycles of style evolution.

Were there any failed sewing machine designs?

Yes, several sewing machine designs failed before widespread success. Thomas Saint’s 1790 patent was never built. Walter Hunt abandoned his lockstitch prototype in

Thimonnier’s chain stitch machines faced durability issues and social backlash during the early sewing wars.

How did sewing machine patents impact other industries?

Sewing machine patents pioneered patent pools—the 1856 Combination cleared blocking claims, enabling industry-wide licensing models.

This innovation diffusion mechanism later influenced aircraft manufacturing and shaped modern intellectual property strategies across technological advancements and industrialization.

How much did early sewing machines cost?

In 1852, household machines commanded $125—roughly $3,700 today—placing them beyond most budgets until Isaac Singer introduced installment plans in 1856, transforming financial barriers and democratizing access during the Industrial Revolution.

Conclusion

Think of the sewing machine as hardware that needed constant software updates—each inventor debugging the last version until Isaac Singer finally shipped a product the world could use.

Understanding when the sewing machine was invented reveals more than dates: it shows how collaboration, competition, and commerce converge to birth technologies that reshape civilizations.

The needle that once moved by hand now powers industries, proving that revolution often arrives one stitch at a time.

- https://www.moah.org/sewingmachines

- https://wunderlabel.com/blog/p/history-sewing-machine/

- https://www.nonameglobal.com/post/the-remarkable-story-behind-the-sewing-machine-s-evolution

- https://www.contrado.com/blog/history-of-the-sewing-machine/

- https://study.com/academy/lesson/history-of-the-sewing-machine.html