This site is supported by our readers. We may earn a commission, at no cost to you, if you purchase through links.

You might think a single genius conjured the sewing machine in one eureka moment, but the truth reads more like a fierce rivalry than a fairy tale. At least five inventors across three continents raced to mechanize the needle and thread, each contributing pieces to a puzzle no one could solve alone.

Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal sketched a double-pointed needle in 1755, Barthélemy Thimonnier opened the first chain-stitch factory in 1830, and Walter Hunt built a working lockstitch machine he never bothered to patent.

Yet it was Elias Howe who secured the 1846 patent that anchored his claim to the invention—a legal stake that sparked courtroom battles and reshaped attribution forever. Understanding who invented the sewing machine means tracing patents, prototypes, and the bold moves that turned tinkering into transformation.

Table Of Contents

- Key Takeaways

- Who Invented The Sewing Machine?

- Early Attempts at Sewing Machine Design

- Barthelemy Thimonnier and The First Factory

- Walter Hunt’s Innovations in The 1830s

- Elias Howe and The Practical Sewing Machine

- Isaac Singer and Sewing Machine Advancements

- How The Sewing Machine Transformed Industry

- Social and Cultural Impact of The Sewing Machine

- Evolution of Sewing Machines to Modern Day

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Conclusion

Key Takeaways

- The sewing machine wasn’t invented by one person—at least five innovators across three continents contributed critical pieces between 1755 and 1851, from Wiesenthal’s double-pointed needle to Howe’s lockstitch patent and Singer’s treadle system.

- Elias Howe’s 1846 patent became the legal anchor for attribution despite earlier working prototypes, proving that intellectual property claims often matter more than who built the first functional machine.

- The technology sparked violent resistance when 150–200 Parisian tailors destroyed Thimonnier’s 80-machine factory in 1831, foreshadowing decades of labor conflict as mechanization threatened traditional crafts and wages.

- By slashing garment production time from 14 hours to one hour per shirt and dropping clothing prices dramatically, the sewing machine democratized fashion while reshaping factory labor, global trade networks, and women’s workforce participation despite persistent wage gaps.

Who Invented The Sewing Machine?

You might think one inventor changed everything, but the sewing machine’s origins tell a messier, more rebellious story. Multiple innovators fought, borrowed, and built on each other’s work across decades, turning a simple idea into an industrial revolution.

Let’s break down the key inventors, what “invention” actually means here, and how patents shaped who gets remembered.

Key Inventors and Their Contributions

You’ll discover the sewing machine’s invention history wasn’t a solo act—it was a rebellion against hand-stitched limitations. Multiple inventor profiles shaped machine evolution through fierce patent wars and technological impact:

- Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal (1755) pioneered the double-pointed needle concept

- Barthélemy Thimonnier (1830) launched the first chain-stitch factory in France

- Elias Howe (1846) revolutionized the industry with his practical lockstitch patent

- Isaac Singer (1851) perfected treadle operation and aggressive marketing strategies

The development of the sewing machine was influenced by key lockstitch innovations.

Defining “Invention” in Sewing Machines

You need to understand that ‘invention’ in sewing machine history isn’t black and white. Innovation criteria weigh multiple factors: did the design evolution deliver mechanical novelty through working prototypes, or just patent laws documentation?

Elias Howe’s lockstitch showed true technological impact by meeting functional standards—consistent stitch formation, reliable feed, sustained operation. Patent alone doesn’t crown an inventor; practical execution does.

The development of the lock stitch mechanism played a pivotal role in the evolution of sewing machines.

The Role of Patents in Attribution

Patent laws transformed attribution by defining inventor rights through enforceable claims. Elias Howe’s 1846 patent gave you a concrete legal anchor—the lockstitch mechanism documented with an eye-pointed needle and shuttle.

When disputes erupted, patent lawsuits forced courts to weigh intellectual property evidence, not just prototype rumors. Singer and others learned this the hard way: without filed claims, your sewing machine innovation vanishes into obscurity.

Early Attempts at Sewing Machine Design

Long before Elias Howe and Isaac Singer became household names, a handful of inventors were already chasing the dream of mechanized stitching. These early pioneers laid the groundwork, even if their designs didn’t quite crack the code of practicality or commercial success.

You’ll see how their experiments, patents, and prototypes set the stage for the groundbreaking machines that followed.

Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal’s 1755 Patent

Before fabric could dance through machines, it needed the right tool—and in 1755, Charles Fredrick Wiesenthal broke ground. This German inventor secured British Patent No. 701 for a radical mechanical needle that sparked sewing innovations:

- Two-pointed design with an eye at one end for reciprocating motion

- First documented patent in sewing machine history

- Component-level advancement that paved industrial roots for future mechanization

You’re witnessing invention’s earliest chapter.

Thomas Saint’s 1790 Invention

Thirty-five years later, Thomas Saint shattered expectations with British Patent No. 1764—the first complete sewing machine design in history.

You’re looking at a chain-stitch mechanism built for leather and canvas, featuring an overhanging arm, vertical needle bar, and looper system.

Though no working prototype survived from 1790, an 1874 reconstruction proved Saint’s blueprint worked, cementing his place in sewing machine history.

Josef Madersperger’s Early Efforts

In Vienna, Josef Madersperger’s relentless pursuit began in 1807, launching decades of mechanical innovations that shaped sewing machine evolution. His 1814 prototype—the first publicly demonstrated device—earned him an imperial privilege, yet funding shortages crushed commercialization dreams.

By 1839, he pivoted to chain-stitch designs, earning recognition but dying penniless in 1850. His early prototypes remain central to innovation history and the invention of the sewing machine.

Barthelemy Thimonnier and The First Factory

While earlier inventors sketched ideas on paper, a French tailor named Barthélemy Thimonnier actually built a working machine and put it to use. In 1830, he patented a device capable of producing chain stitches, and he didn’t stop there—he established the world’s first sewing machine factory.

His advancement, however, triggered a backlash that would reveal just how disruptive this technology really was.

Chain Stitch Mechanism

Thimonnier’s chainstitch sewing machine revolutionized sewing technology through its hooked needle design, producing tambour-style seams at roughly 200 stitches per minute. Unlike the lockstitch mechanism Elias Howe would later perfect, chain stitch formation created interlooped single-thread structures—boosting sewing speed dramatically but demanding higher thread consumption.

You’ll notice fabric elasticity improved by 30%, though machine reliability suffered when stitches unraveled without proper sealing.

Industrial Impact in France

By 1830–1831, you’re witnessing France’s Industrial Revolution take a decisive turn: Thimonnier’s Paris workshop deployed roughly 80 machines, mass-producing French Army uniforms at one-third the cost of hand sewing. This factory organization marked the first mechanized garment operation in Europe, embedding invention and innovation into manufacturing and technology.

Economic development accelerated as machine productivity reshaped French textile growth, standardizing workflows and fueling the textile industry’s transformation.

Resistance and Factory Destruction

Innovation doesn’t always spark celebration—sometimes it ignites fury. On January 20, 1831, 150–200 Parisian tailors stormed Thimonnier’s Rue de Sèvres workshop, driven by mechanization fears and economic protests over vanishing wages and jobs.

On January 20, 1831, 150–200 Parisian tailors stormed Thimonnier’s workshop, their fury over vanishing jobs igniting the violent birth of industrial resistance

Here’s what unfolded in this critical moment of labor unrest:

- Factory riots destroyed approximately 80 machines in organized industrial sabotage

- National Guard and infantry intervened, arresting 75 defendants for property destruction

- Court sentences ranged from eight days to one month for public-order violations

- Thimonnier retired immediately, his enterprise collapsing amid anti-mechanization violence

- Patent disputes would later haunt Elias Howe during similar Industrial Revolution tensions

This catastrophic event became textile industry legend, foreshadowing decades of conflict between artisans and mechanized production.

Walter Hunt’s Innovations in The 1830s

You mightn’t have heard of Walter Hunt, but his work in the 1830s quietly laid the groundwork for the sewing machine as we recognize it.

While others raced to patent their designs, Hunt built something extraordinary—then walked away from it.

Let’s look at what he created, why he never claimed it, and how his ideas shaped the machines that came after.

Lockstitch Mechanism Development

Hunt’s lockstitch design broke the mold by interlocking two threads—one from an eye-pointed needle, the other from a shuttle beneath the fabric—creating a secure seam that wouldn’t unravel.

This machinery innovation, built around 1833–1834, introduced enhanced stitch formation and thread tension control, setting the stage for Elias Howe’s later lockstitch design.

You’re witnessing the blueprint that revolutionized sewing speed and fabric compatibility.

Reasons Hunt Did Not Patent His Machine

Despite perfecting his lockstitch innovation, Hunt never filed for a patent in the 1830s. Financial Barriers and Moral Concerns collided—he feared displacing seamstresses, including those at his daughter’s corset shop, while startup costs of $2,000–$3,000 (around $63,000–$94,000 today) proved prohibitive.

This Abandonment under Patent Laws opened the door for Elias Howe to secure the 1846 patent, forever altering the History of the Sewing Machine and redefining Patent and Intellectual Property dynamics despite Hunt’s earlier Invention of the Sewing Machine amid Market Resistance.

Influence on Later Designs

Though Hunt never commercialized his work, you’ll find his lockstitch blueprint echoing through every machine that followed. Howe’s 1846 patent and Singer’s 1851 improvements borrowed Hunt’s two-thread architecture, sparking sewing machine patents that defined Design Evolution and Mechanism Improvements.

His unpatented Sewing Innovations accelerated the Evolution of Sewing Technology, proving that even abandoned ideas can reshape Industrial Sewing Machines and Modern Advancements in Sewing forever.

Elias Howe and The Practical Sewing Machine

While earlier inventors laid the groundwork, Elias Howe broke through where others had stalled. Born in Spencer, Massachusetts, in 1819, Howe spent five years perfecting what would become the first truly practical sewing machine—one that didn’t just work in theory but could actually transform how you made clothing.

Here’s how he turned years of struggle into an advancement that changed everything.

1846 Patent and Lockstitch Mechanism

You’ll want to understand the Patent Details behind Elias Howe’s revolution. On September 10, 1846, he secured U.S. Patent No. 4,750, cementing his legacy in the Biography of Elias Howe. His Lockstitch Design changed everything through these Mechanism Fundamentals:

- Eye-pointed needle creating thread loops for interlocking

- Shuttle operating beneath fabric for reliable Stitch Formation

- Automatic feed maintaining uniform spacing

- Two-thread lock stitch configuration ensuring durability

This Sewing Machine Design distinguished his work from earlier chain-stitch attempts, marking the true Invention of the Sewing Machine and establishing foundations for all Sewing Innovations that followed.

Challenges and International Recognition

Patent Barriers plagued you from the start—Howe’s 1846 invention faced Legal Battles until 1854, when Singer finally lost in court.

Market Recognition arrived through Royalty Streams as firms paid $5 per machine.

International Recognition came at the 1867 Paris Exposition with a gold medal and France’s Légion d’Honneur, cementing the Industrial Revolution Impact and Social and Economic Impact of this revolutionary innovation.

Isaac Singer and Sewing Machine Advancements

While Elias Howe secured the first practical sewing machine patent, Isaac Singer transformed the invention into a household revolution.

Singer didn’t just enhance the mechanics—he reimagined how you’d actually use the machine and built an empire around it. His 1851 improvements, aggressive marketing tactics, and fierce legal battles shaped the sewing machine industry as people recognize it today.

Singer’s Patented Improvements in 1851

You’re about to discover how Isaac Merritt Singer’s 1851 patent transformed the sewing machine from a temperamental curiosity into an industrial workhorse. His U.S. Patent No. 8,294, granted August 12, revolutionized machine design through:

- Vertical straight-needle mechanism replacing unreliable curved needles

- Foot treadle drive freeing both hands for fabric guidance

- Enhanced lockstitch tightening via forward shuttle motion

- Adjustable thread tension control reducing breakage

These sewing innovations delivered up to 900 stitches per minute, redefining stitch technology and industrial impact.

Marketing and Mass Production

Beyond technical brilliance, you’ll see Singer’s empire rose on audacious mass marketing moves. He unleashed door-to-door demonstrations, slashed prices from $125 to $30 through optimized manufacturing process efficiency, and pioneered installment payments—letting households own machines for pennies weekly. His global expansion built proprietary retail chains across Europe and Russia, while industrial sewing machines flooded factories. This brand management revolution turned sewing technology into a household necessity.

| Sales Strategies | Market Research Impact | Mass Production Result |

|---|---|---|

| Rent-to-own plans (1850s) | Tripled sales 1855–1856 | Factory output soared |

| In-home demos by canvassers | Unlocked household demand | Costs dropped to $30 |

| Owned global retail offices | Russia became top market | Millions produced annually |

| Award-winning exhibitions | Paris 1855 validated quality | Brand dominated worldwide |

Patent Disputes and Legal Battles

In 1851, triumph met turmoil when Isaac Merritt Singer’s invention triggered a decade-long patent war with Elias Howe Jr. Sewing machine litigation exploded across courtrooms, intellectual property claims clashing until court rulings forced Singer to pay Howe $25 per machine after 1854. These legal battles reshaped the industry:

- The “Sewing Machine War” consumed tens of thousands of testimony pages

- Settlement royalties totaled $15,000 upfront plus ongoing fees

- By 1856, rivals formed America’s first patent pool to end the chaos

How The Sewing Machine Transformed Industry

The sewing machine didn’t just change how clothing was made—it rewired the entire industrial landscape. From factory floors to global trade networks, this invention sparked a manufacturing revolution that reshaped economies and workforces across the world.

Here’s how the sewing machine transformed industry from the ground up.

Acceleration of Garment Manufacturing

When you consider the textile industry’s leap forward, sewing automation didn’t just tweak garment production—it shattered every limit. Thimonnier’s 1830 chain-stitch machine hit 200 stitches per minute against hand sewing’s mere 30, while Howe’s lockstitch design outpaced five manual workers combined.

Factory optimization through machine sewing compressed labor inputs dramatically, fueling mass production and industrial efficiency across the entire manufacturing process.

Standardization and Mass Production

You’ve witnessed speed—now meet the architecture of scale. Singer’s manufacturing revolution wasn’t just about faster stitching; it rewrote the entire industrial playbook through precision and global coordination.

- Patent Pooling (1856): The Sewing Machine Combination unified lockstitch patents, forging industry-wide standards that dominated until 1877

- Standardized Parts: Interchangeable components slashed prices by 50%, enabling mass production that reached 500,000 units by 1880

- Global Networks: Singer’s worldwide factories and service depots replicated standardized designs, commanding 80% market share by the early 20th century

This mechanization turned sewing machines from artisan craft into automation’s triumph.

Economic and Workforce Changes

Economic shifts cascaded through factories as mechanization of labor redrew employment maps. By 1860, a men’s shirt—14 hours by hand—took just one hour by machine, accelerating industrial growth but squeezing wages for displaced artisans.

The textile industry boomed: ready-made clothing output jumped from $40 million (1850) to $70 million (1870), fueling factory expansion while reconfiguring who stitched and who profited.

Social and Cultural Impact of The Sewing Machine

The sewing machine didn’t just change how clothes were made—it reshaped who made them, who could afford them, and how society viewed fashion itself.

From factory floors to family homes, this invention sparked shifts in labor, economics, and cultural expression that rippled across generations.

Here’s how the sewing machine transformed the social fabric of the 19th century and beyond.

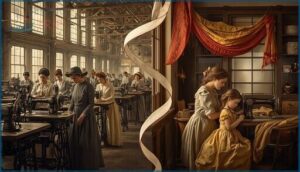

Empowerment of Women in The Workforce

The sewing machine’s mechanization reshaped women’s labor rights during the Industrial Revolution, pulling you into factories where textile industry roles multiplied. By the 1860s, 400 women on machines replaced 2,000 hand sewers—yet female employment faced a stubborn gender wage gap.

Factory wages reached $3–$4 weekly versus men’s $12, revealing that workforce equality lagged even as garment industries offered new economic independence through mechanized work.

Accessibility of Affordable Clothing

Your wallet felt the difference when mass production slashed clothing prices—apparel today costs five times more nominally than a century ago, yet you’re spending far less relative to income.

Fast fashion accelerated this shift: between 2000 and 2014, your per capita purchases jumped 60% as affordable apparel flooded global markets, democratizing garment manufacture beyond what Industrial Revolution pioneers imagined possible.

Influence on Fashion and Society

Fashion trends accelerated beyond recognition once machine production shortened design-to-market cycles. You witnessed cultural impact ripple through every social stratum—garment production democratized style itself, erasing class distinctions that once defined wardrobes.

The textile industry didn’t just manufacture clothing faster; it rewired social hierarchies, letting you signal identity through fashion choices rather than inherited status, fundamentally reshaping how society expressed itself through dress.

Evolution of Sewing Machines to Modern Day

The sewing machine didn’t stop evolving after its 19th-century advancement—it kept pace with every wave of technological change that followed. From the introduction of electric motors to today’s computerized systems, you’ll see how these machines adapted to meet the demands of both home sewers and industrial manufacturers.

Here’s how the sewing machine transformed from a mechanical marvel into the refined tool you recognize today.

Transition to Electric and Computerized Models

You’ve witnessed a revolution from manual treadles to machines that think for themselves. Singer broke ground in 1889 with the first practical electric sewing machines, replacing foot power with electric motors. By 1978, computerized controls arrived through Singer’s Touchtronic 2001, while Brother launched the Opus 8 in 1979, ushering in an era of digital stitching and automated sewing that transformed production floors and creative spaces alike.

- Electric Motors eliminated physical labor, with Singer offering portable electric models by 1921 as household power access expanded

- Electronic Interfaces emerged in 1975 with the Athena 2000, introducing programmable needle positioning and automated thread cutters

- Computerized Controls enabled stitch memory and on-screen pattern selection throughout the 1980s–1990s, democratizing precision

- Technological Advancements continue driving growth, with the computerized embroidery market projected to reach $1.8 billion by 2034

Home Vs. Industrial Sewing Machines

Today’s machine comparison reveals a sharp divide in sewing techniques and capabilities. Industrial models—built for garment industry demands—hit 5,500 stitches per minute with automatic lubrication, servo motors boosting energy efficiency, and fabric handling systems for continuous production.

Your home sewing machine? It peaks around 1,100 stitches per minute, prioritizing versatility over speed, with lower maintenance costs but intermittent-use design inherited from the industrial revolution and sewing innovations that sparked this technology.

Continuing Legacy in The Textile Industry

The textile industry races ahead with digital sewing tools rewriting manufacturing efficiency—your garment industries now deploy IoT sensors and AI fault detection that slash downtime.

Industry growth surged from $4.56 billion in 2024 to a projected $6.20 billion by 2030, driven by sewing innovations in computerized pattern control and sustainability-focused designs that echo textile trends demanding speed without waste.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Who invented the original sewing machine?

The invention origins trace back to Thomas Saint, who designed the first sewing machine in 1790, though Elias Howe earned the 1846 patent for the practical lockstitch model that revolutionized industrial impact.

Who invented the sewing machine in 1793?

No one invented a sewing machine in 1793—a common Invention Myth. Patent History shows Thomas Saint’s 1790 design preceded Barthélemy Thimonnier’s 1830 practical machine, clarifying the history of sewing machines and Machine Evolution timeline.

Did Elias Howe invent anything else?

Beyond lockstitch glory, Howe glimpsed fasteners unborn—his 1851 Closure Mechanism patent sketched the zipper’s DNA.

Yet Patent Strategies focused him on sewing machine royalties, not NonTextile Inventions, leaving Mechanical Innovations to Singer and successors.

Who invented Singer sewing machine and when?

Isaac Merritt Singer received U.S. Patent No. 8,294 on August 12, 1851, securing his sewing innovations. His machine evolution transformed industrial impact through practical improvements—vertical needle, lockstitch shuttle, and treadle power—revolutionizing garment production.

When did electrically powered sewing machines become mainstream?

You might assume electric sewing machines instantly replaced treadles, but household electrification constrained their spread. Singer’s 1889 electric models gained urban adoption in the 1920s, then mainstreamed nationwide after rural electrification accelerated post-1936, normalizing by mid-century.

What influenced Elias Howe to invent his machine?

Your curiosity about invention starts with noticing a problem others overlook. Industrial exposure at Lowell mills, mentorship under Ari Davis, and domestic observations of hand-sewn piecework converged, pushing Howe toward innovation amid competitive pressures from early sewing machine attempts.

How did the sewing machine affect gender roles in the workplace?

The sewing machine revolutionized garment manufacture, yet mechanization of labor entrenched workplace inequality.

Female labor flooded textile industry development but faced gender pay gaps, while women empowerment remained limited despite the sewing machine’s impact on industrial growth.

What materials were early sewing machines designed for?

You’ll find that early sewing machine designs targeted leather and canvas—think boots, saddles, and ship sails. Thomas Saint’s 1790 machine pioneered heavy-material handling, while later innovations shifted toward woven fabrics for garment manufacture.

How did patent disputes affect sewing machine development?

Imagine courtrooms packed with attorneys arguing over a needle’s eye—that’s how Patent Wars erupted. Litigation Outcomes forced Isaac Merritt Singer to pay Elias Howe royalties, while Industry Impact led to the first Patent Pools, transforming sewing machine development permanently.

When did electric sewing machines first appear commercially?

Singer introduced the first electric sewing machine commercially in 1889, marking a revolution in automation and industrial electrification. Electric motors replaced hand-crank and treadle power sources, though widespread adoption required decades of infrastructure development.

Conclusion

You might expect a neat origin story, but who invented a sewing machine defies simple answers. The machine wasn’t born; it was forged through rivalry, litigation, and relentless iteration.

Wiesenthal’s needle, Thimonnier’s factory, Hunt’s lockstitch, Howe’s patent, Singer’s empire—each inventor built upon what predecessors left unfinished.

That messy lineage proves innovation rarely springs from solitary genius. Instead, it emerges when ambition collides with necessity, transforming thread and fabric into the backbone of modern industry.

- https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/destitute

- https://www.sil.si.edu/DigitalCollections/trade-literature/sewing-machines/pdf/sewing-machines.pdf

- https://ncert.nic.in/vocational/pdf/ivsm101.pdf

- http://content.time.com/time/subscriber/article/0,33009,960805,00.html

- https://www.britannica.com/technology/sewing-machine